The oversight of charter schools has changed dramatically from the beginning of the movement. States and authorizers are applying increasingly sophisticated tools to assess the performance of the schools they oversee. A key concept that helps authorizers do their jobs well is differentiation. This concept informs the increasing use of Performance Frameworks. Under a differentiated system, schools are divided into groups. Often they fall into five categories. These categories represent schools that:

- Should close as soon as possible;

- Are struggling, but might improve;

- Are meeting expectations but not exceeding them;

- Amaze us, and ought to replicate if they are willing and able; and

- Are unique because of their mission and student population, and consequently require specialized evaluation.

By distinguishing among schools based on how well they are doing, and treating schools with different performance differently, authorizers are better able to make the types of high-stakes decisions that modern authorizing requires. Once the schools are differentiated, the authorizer faces different kinds of work for each group of schools.

The work of differentiating among schools is generally captured by school performance frameworks. These are tools that strong authorizers are developing and that NACSA has put a great deal of effort into supporting. In the coming years, differentiation and well-crafted performance frameworks are going to be more and more wide-spread among strong authorizers.

The differentiated approach to school quality differs from the two alternatives that predated it. When evaluating traditional schools, states and districts used a standardized approach. This approach primarily determined which schools were not meeting a standard. It produced a “pass/fail” system. Authorizers applying this standardized approach can identify schools that are in trouble, but not much else. For traditional schools systems, this morphed into a measure of Adequate Yearly Progress, which schools did, or did not, achieve.

Two emerging themes in charter quality can get side-lined by this old pass/fail approach. People want to close the schools that are terrible, and they seek to replicate the schools that are amazing. Sometimes they act as if there were no schools in between those extremes. But the truth is that many charters are not bad enough to close, nor good enough to replicate. Recent proposed priorities for the administration of the federal charter school program echoed this replicate or close fallacy. The language defined “quality charter schools” based on a standard for what would deserve replication, and then implied that all schools that didn’t reach that replicable standard should not be in any authorizer’s portfolio. That is a case of misunderstanding modern performance management.

For many authorizers, the early efforts at accountability in the charter movement were different from a pass/fail system applying one standard. Authorizers and school leaders often thought of each charter school as a wholly unique institution, deserving an individualized approach to accountability. As special cases, each charter school was measured with accountability measures created specifically for it based on its own charter application. Or, if authorizers were unable or unwilling to individualize measures, the charters were measured with the single and undifferentiated tool of the standardized traditional system.

The new system of differentiation is a hybrid. It allows a degree of standardization among groups of similar schools. This standardization within groups of similar schools makes the approach viable and realistic for schools and authorizers. Importantly, it also provides comparability and the ability to apply minimum state standards across the sector. This is especially important as the sector has grown and challenges in quality have been more obvious. Meanwhile, differentiated systems allow authorizers to respond to each school, based on how well it performs and what it is trying to achieve.

This emerging approach allows authorizers to make the hard decisions they face. Differentiating among charter schools based on their performance can help achieve many goals in the charter sector. It can:

- Support the timely closure of failing schools;

- Focus authorizers’ attention on schools that are the trickiest to understand;

- Reduce the burden on successful schools, allowing them to focus their time and resources on their students;

- Identify the best schools that should be encouraged to replicate their programs so they can serve more students; and

- Ensure unique schools with special populations are evaluated appropriately.

An under-appreciated aspect of this approach is that once the schools are assigned to these five buckets, for most of the schools, an authorizer doesn’t need to know a great deal of subtle details about the rest of their academic performance. It is important for authorizers to dive deeper into the data on some schools, which we can identify below. And it is key for other people besides authorizers to examine performance of most schools at a micro level. But the finer-grained data on performance would not change what an authorizer would do for most of the schools in their portfolio.

Other people need more detailed analysis of performance certainly. School operators and their governing boards, for example, can benefit from a much deeper dive. But authorizers can focus. By defining a more narrow set of what an authorizer is responsible for measuring and evaluating, we can help authorizers get better at the tasks that follow.

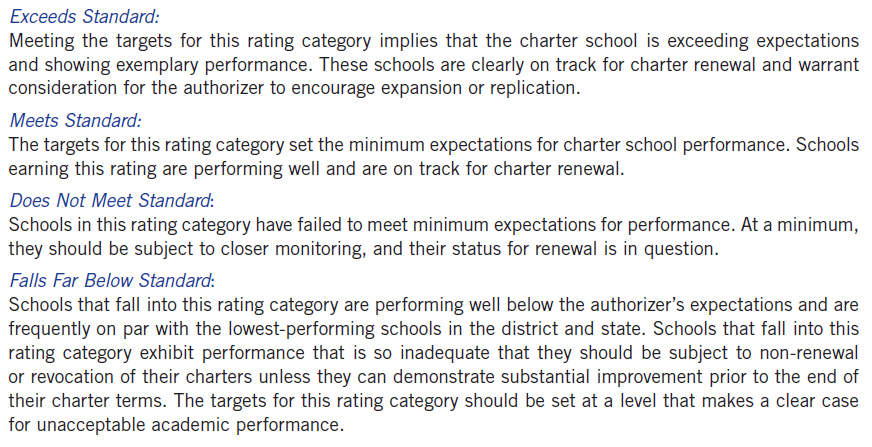

Authorizers place schools in four of the five buckets based on their performance. Evaluation is generally based on academic performance, but authorizers can move schools down based on governance, operations and financial problems as well.

Truly bad schools belong in the bottom bucket. These schools need to close, and quickly. Preferably, they would close at the end of the current school year. If the school is up for renewal this year, its renewal should be denied. If their charter term is not up for a few years, their charter should be revoked before the end of their term — and before more kids are harmed.

The second tier of schools is only doing slightly better. Their performance is problematic, but it is not so weak that an authorizer needs to close them immediately. When charter terms are five years long, the schools in the second bucket may not need to close immediately; but they should not be renewed unless they improve significantly before their term expires. An authorizer must regularly identify these schools, make clear that their current performance is unacceptable, tell them how long they have to improve, and how much better they must get within that time-frame if they are going to be allowed to stay open. Authorizers also need to understand the performance of these schools intimately so that they can assess whether improvements are real and likely to be sustained. Renewal decisions should be made based on a school’s record of performance, not promises about the future.

The third tier of schools is doing relatively well. These schools are meeting their performance expectations and an authorizer would renew them if they came up for renewal today. Authorizers should identify these schools and make clear to them and the public that they are acceptable but not exceptional. In terms of high-stakes accountability, the authorizer’s remaining task for these schools is to monitor their performance to ensure that it improves or at least doesn’t decline. In many jurisdictions, the majority of charter schools are in this category. They may need to improve, but it is up to them and not the authorizer to make that happen. Authorizers should never let schools coast along until renewal time but neither should they pretend that they know more than schools themselves about what it takes to improve. Clarity about schools in the middle would save both authorizers and schools from lots of over-reaching and overbearing behavior and would help differentiate those schools that truly are failing to meet expectations from those that are performing acceptably, even if they should and could do better.

The fourth, or top, tier of schools is hitting it out of the park. The schools in this bucket are performing exceptionally well. These are the schools that an authorizer– and most other stakeholders in their community–hold up as examples of what is possible. Authorizers need to identify these schools, highlight their performance, and enable their continued success.

Authorizers interested in portfolio management will likely have an interest in studying these high-performing schools more, but for different reasons. Many want to explore replication, or they want to analyze what is working so well. Not all great schools want to replicate, or are ready to do so. But some districts, like Denver Public Schools, are starting to see real and measurable benefits when they encourage their best-performing charters to take on more schools and more kids. District authorizers that operate their own schools may also want to explore what they can learn from, or copy, in this school. Even authorizers that are not districts and do not have the option of copying the school, would further one goal of the charter sector by sharing what they can learn about these schools and explore how to help others use these successful strategies to benefit more kids. And all authorizers can and should work to remove barriers to the growth and replication of high performing schools. After all, more high performing schools means more quality opportunities for kids.

The fifth bucket is for schools with a specific mission and a student population. These schools are focused on extremely at-risk students — like dropouts, incarcerated youth, or pregnant and parenting teens. Some states give the schools in this bucket names like Alternative Education Campuses (AEC), or some other local variation. The authorizers’ job is first to identify which schools belong in this bucket and which do not. A recent report from NACSA by a national task force looking at AECs provides a strong set of recommendations regarding these schools.

Often, the trickiest part is not identifying AECs, but enforcing a standard that keeps other schools from claiming they belong in this bucket too, when that designation would be wrong. Failing schools that are not AECs want the designation so they can avoid the sanctions associated with their unacceptable performance. AECs with performance that appears unacceptable, may be doing a good job with their population, or they could just be as bad as they look.

Differentiation is an emerging approach that is helping authorizers focus on the type of work they are supposed to do in their own unique role as authorizers.