Courtroom Leads Back to Classroom

When I worked for Chicago Public Schools, I worked for some lawyers. I felt as if I needed to gain the knowledge and the capacity to understand the School Code, and to be able to articulate and persuade using that Code and using case law, so I felt like I needed to go to law school…

I go to law school, and I decide that I need to practice. I need to gain some trial experience and have experience in the courtroom. So, I become a prosecutor. Day in and day out, I was reminded how important education is because I was able to see youth come in and out of the courtroom for minor violations. But those violations would impact their lives—dictate the next path of where they could go and where they couldn’t go. I just felt like, “How do you remedy this?”

Then I was brought back: it all starts with education. I looked at the communities that fed into that courtroom and what didn’t they have? They didn’t have access to high-quality education.

That’s what sort of brought me full circle back to it. So the reason why I’m able to look at these same issues 10 years later is because I now have a different perspective, from a different vantage point, as to why education is important.

A Great Homegrown Charter Story

My grandfather was from Baton Rouge, and he migrated to Chicago. And I always think that I’m kind of circling the wagon and going back through his past.

I was in Chicago, and I went back to Louisiana where he is from [Shenita lived and worked in New Orleans pre-Katrina, and returned to New Orleans when she worked for NACSA post-Katrina].

I just remember looking at the television during Hurricane Katrina and just seeing the destruction and the lives that were affected. To have that opportunity to go back: I couldn’t turn it down. I thought, who else is being offered this opportunity to do this work, that I know how to do, that has meaning to me? ‘I have to do it. I can’t not do it.’

I remember one school that applied [to be a charter school in New Orleans] was the Martin Luther King Elementary School. It was an elementary school in the 9th ward—one of these schools that’s the hub of the community. It was just a regular school; it wasn’t a magnet or a selective [school], but a good-performing school that had a lot of support…

They applied. I remember, for the interview: we tell them [the applicants] to bring 5-8 people for the interview. You don’t need to bring a lot of people. Of course, they bring all of their supporters and everybody’s got on these t-shirts, and I think, ‘Okay, great…’ A lot of people thought, ‘They don’t have this management company behind them…’ Their track record of success was the school that was operating under the previous administration, but their application was evaluated, and the school was recommended for approval. It was just really a great homegrown story of the community being involved and wanting their school back.

I remember the principal: you know, she’s a traditional school principal. She said, ‘I’m kind of interested in this charter… I know I want my school back, so we’re going to do it.’ I think the charter also gave them autonomy they didn’t have before, so they were able to do different things that they weren’t able to do as a district [school].

In the Best Interest of All

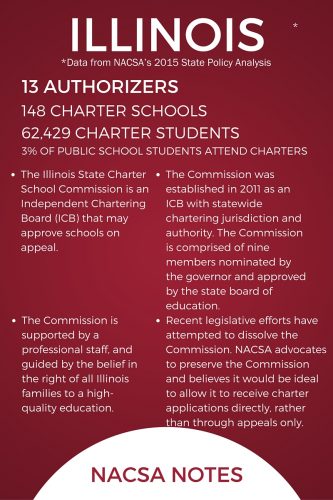

The Illinois State Charter School Commission: we don’t receive direct applications, and we don’t release an RFP to create schools. The Commission only approves schools by appeal.

If a school, or an applicant for a charter school, makes a proposal to the local district and the district denies it, then the applicants have the opportunity to appeal to the state—the state commission. The state commission reviews those proposals and decides whether or not they meet the law and whether or not the schools are in the best interests of the children in that local community.

That puts us in a very unique position, because the district has certain feelings about what [the Commission is] doing. Number one, they don’t think that a state agency should have the ability to decide what happens in their local district.

But again, from my experience working as a prosecutor, everybody gets their day in court, right? Everybody has an opportunity. Just because one group makes a decision, [there should be] an opportunity to appeal that decision in some way and the Commission is the body [that listens to the appeal].

And there’s also the benefit, again, of engaging and educating applicants about what is high quality… It’s our job to make sure that that proposal meets the law and is high quality and is in the best interest of all students in the communities.