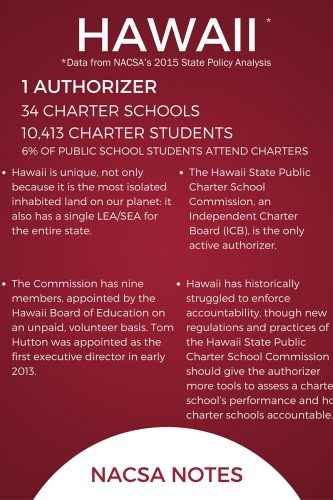

Watch and read edited excerpts of our Story Suite conversation with Tom Hutton, Executive Director, Hawaii State Public Charter School Commission. NOTE: Shortly before releasing this, NACSA learned of Tom’s decision to resign from this post, at a date not yet determined as of this posting.

Watch and read edited excerpts of our Story Suite conversation with Tom Hutton, Executive Director, Hawaii State Public Charter School Commission. NOTE: Shortly before releasing this, NACSA learned of Tom’s decision to resign from this post, at a date not yet determined as of this posting.

Task One: Accountability

NACSA: What keeps you going on those days where you feel like, ‘Wow. There’s still so much work to be done and so many barriers to making that happen’?

Tom: I think it’s the potential. I mean, you have to look for it and say, ‘We’re not there yet, but we do have some highly successful charter schools.’ That is where we would like them all to be. When we have a very high-performing charter sector, I think there are insights for the larger system there. And there already have been; even, frankly, with some of our schools that are not that successful academically, there are things that they have done that are highly successful and that the system has learned from already.

We have one statewide school district. So the fact that there are alternatives and people trying new things and different things in our state is critically important where you only have one school district to begin with. I think that there really is the potential.

It’s still very hard right now because the whole notion of the charter bargain and the accountability is still something new, frankly, in our charter system. It rankles some of our longer-term school leaders—the idea that we’re [the Commission is responsible for] oversight. The previous entity was seen as their support organization, and while we are very supportive and we are strengthening the system overall, our task one is accountability. Very clearly, that’s what the legislature has mandated, and that’s hard for schools that aren’t used to that being how it works, and we’re still navigating that very difficult path.

But I’m still optimistic that the system will continue to improve and that will yield benefits that the schools themselves will see. Some of them are already there, but a vocal portion of them are not. Just imagine if we were not having such contention about this stuff, but just all pulling in the same direction, what we could accomplish. I hope that we will turn the corner on that and be able to show that, because the potential is clearly there.

‘Our Job is to be the Truth-tellers’

NACSA: It’s got to be a hard balance: the accountability piece is a priority, but you do still want to be a source of support as the authorizer to these schools. How do you do this?

Tom: The way we try to do it is we identify as priorities for support the things that are needed to make the system work, versus ‘I am the advocate of maybe what this particular school wants or even a group of schools necessarily want.’ If it’s something where this systemically is not working: now, that’s fair game for us. The legislature does look to us for our perspective on those system sorts of things. And so, I will say that the work is really a monumental task.

And because just getting the basic sort of accountability structure in place is still such a heavy lift, we are not doing a good enough job of making sure the schools know how much we’re also pushing for things like facilities funding—they don’t see that side. They see the ‘scary’ side of us, and maybe individual schools see what we did about this situation or that situation, but we don’t spend a lot of time blowing our own horn to the schools and saying, ‘We got this done. We got this done. We got this done.’

Maybe we need to. I guess our philosophy has been: do the work and the results will speak for themselves. Don’t take time away from the work to brag about the work. But, you do have to do some of that if your schools aren’t to get the [wrong] impression. The only time we see the commission in the news is when you talk about [how] you had to close a school. They only see this negative, scary side of things; we need to invest some more in that in terms of the relationship building and telling the story of what we’re doing…

…There was a reason why the legislature said, “Accountability: job one.” I do think that there are times when we’re supporting changes. We do want to tell the good stories of chartering and its potential, but we are not the PR agency for every good thing happening in charters.

That actually, I think, helps us to a degree with our credibility and our advocacy for the system as a whole. When we do an annual report that just gives you the straight, unvarnished, ‘You know what? The charter sector is underperforming relative to the larger system.’ Let’s be very clear about it, put it right out there. [But] half of our top high schools are charter schools: when we bragged about [that] after we’ve just said, ‘Let’s be clear. We’re not where we need to be,’ that positive message has twice the credibility because they know that we’re not just being a PR agency for charter schools. Our job is to be the objective truth-tellers in all of this.

Starting a School for the Right Reasons

Starting a School for the Right Reasons

Tom: When I went to law school as a grey-haired law student, I was gravitating toward educational kinds of things in law. There was a group of law students at my school: we proposed our own seminar on education law and reform… And we said, ‘[We] want to learn about education? Let’s start a school.’

They [Georgetown University Law Center] had a clinical program in which law students teach a Street Law course in the public schools. Several of them [law students] were dismayed about what they found in some of the schools that they were serving. Showing all the hubris of youth, [we] said, “You know, we could design a school that could do better than this,” and we did… This group of law students—we applied to the D.C. Charter School Board to start a charter high school, which is there to this day: Thurgood Marshall Academy… I served on the board of the school initially…

NACSA: You were in law school. That alone is consuming and challenging. Why did you think that that was a good use of your time, to be part of this group to craft a new school? What were you hoping to accomplish?

Tom: When you live in a place like [Washington] D.C., which has this incredible wealth and a highly educated population next door or usually overlapping with a very disadvantaged, very impoverished population with not a lot of education, you can’t just ignore that contrast. [We asked:] ‘Is there some way that we can contribute to doing something about that in our little way?’ There was a tool available to us in this thing called ‘chartering.’ …you could already tell early on that this was headed for some kind of success.

NACSA: How?

Tom: D.C. has a very large legal community, and we decided to tap into that. So, we had lawyers as mentors, as tutors. We had law firm sponsors that really leveraged the public funding that we were getting with quite significant private funding to bring more resources to bear to the kids who needed them most.

…It’s been years since I’ve been in direct touch with it and I’ve lived far away, but they have a very impressive track record of getting their graduates into post secondary school. These are, many times, children who have no college in their family tree, any parent. Then the next challenge became, we want to make sure they get through [college]. And so, taking ownership of all kinds of things: it’s not just enough to build a school with a great program when kids are facing these kinds of barriers to their success. That involved everything from, if we needed to help the parents do their taxes because that’s the only way that the kids can qualify for financial aid, well, I guess that’s our responsibility too. All that wraparound needs to happen in order for kids to, in some situations, to be able to succeed educationally.

We deliberately targeted Ward 8 in the District of Columbia, which is a very economically depressed ward. We were a bunch of [mostly] white kids from Georgetown. So we were outsiders. And you know, I think it’s sort of: you do it, you show that you can do it, and that you’re doing it for the right motivations… You just prove yourself. We had a lot of sort of soul-searching conversations about if we appoint the leadership of this school and it’s not African-American… You have to just be overt and confront that, because it’s a real issue.

But, ultimately, parents want a good education for their kids. This was a community that was used to people coming in and making great promises: they can get a grant to go into Ward 8, [but] the grant disappears, and the people disappear. So, part of the trust building was making sure that people knew that we were there to stay.

Taking a Risk to Commit

Tom: When we moved back [Tom worked in Hawaii state government post-college, then left the state for law school, an eight-year stint as an in-house lawyer for the National School Boards Association, and a few years in private practice in Seattle before moving back to Hawaii over three years ago], six months after I got there [Hawaii], the Commission was looking for its first executive director. And the head hunter found me—I’m still not entirely clear how, except Hawaii’s a very small place.

I initially was very cool to the idea. They had rebooted the charter sector for a reason. The predecessor agency—the executive director job—was sort of a revolving door: it had chewed up a lot of people. This was my reentry, this is my professional reputation, and I had to really think hard about it. It’s kind of risky.

But speaking of the stars being aligned: I had read that they were redoing things and I thought very well of our board of education. We had a new appointed board that was really doing good things. We had a superintendent who I really admire and have known for a long time. The right people in the right seats in the legislature where I just thought, ‘You know what? Talk about a commitment to a place!’ It kind of loops back to that whole earlier conversation of working in state government.

Public education is challenged in Hawaii, and it [Hawaii] is a crushingly expensive place for people to be thinking, “Well, I’ve got to go pay for private school tuition too.” I think chartering really has the potential to have a catalytic effect in our state. It’s an unrealized potential now. We have our challenges and work to do still, but that’s kind of where it could lead, in my view: How do we impact systemically what’s happening with public education in our state?