Here are edited excerpts of Part 1 of our Story Suite conversation with Gail Greely, director of the Charter Authorizers Regional Support Network, a program of the Alameda County Office of Education. Part 2 here.

Here are edited excerpts of Part 1 of our Story Suite conversation with Gail Greely, director of the Charter Authorizers Regional Support Network, a program of the Alameda County Office of Education. Part 2 here.

Intrigue Leads to Charters

NACSA: How did you get into this piece of public ed?

Gail: Education is really a second career for me. I was an energy lawyer for 20 years. But when my oldest was getting ready to go to school, I started trying to learn more about the district and the local school. I got on the school advisory committee [the School Site Council] at our local school and then got drafted to be on the bond committee. In one night of just overenthusiastic response to some stuff that was going on in the school district, I decided to run for school board.

NACSA: This was in what town?

Gail: This is in the City of Alameda. Which is an island off the coast of Oakland.

NACSA: It’s an island?

Gail: It’s an island, yes. The Isle of Style. Also known as Nebraska by the Bay. So I ran for the school board. I ended up serving two terms on the school board, so eight years of service as an elected official. By the time I got to the end of it, I felt like I wanted to keep going in education. I’d really gotten tired of the energy business. It was becoming kind of an ugly business actually at the time. It was when Enron was imploding.

I had the opportunity to go to work for a nonprofit that wanted to start a charter school. One of the reasons I was so intrigued by that was because during eight years as an elected school board official, I had seen efforts to do significant school reform fail or sputter or start and then get killed because there was a change in administration.

It was just so frustrating. The city is one of those places that has the ‘right and the wrong side of the tracks,’ and it was just so frustrating to see the consistent gaps in performance, in funding, in focus between the affluent and the low income ends of the town. So I was intrigued by the whole charter school theory.

This was pretty early in the movement. I ended up working for 10 years as a charter school leader in two different organizations.

New Role in ‘The Charter Wars’

Gail: And then [after a couple of years as an authorizer in the Oakland School District Charter Office] the opportunity came up to go to the Alameda County Office of Education [ACOE] and authorize with a smaller portfolio, but with a larger brief.

Our superintendent at the county level at that time was very interested in supporting the other authorizers throughout the county, was interested in being a leader. She had, early in the movement, actually convened a meeting of charter advocates and district personnel to try and start working through some of the issues in ‘the charter wars.’

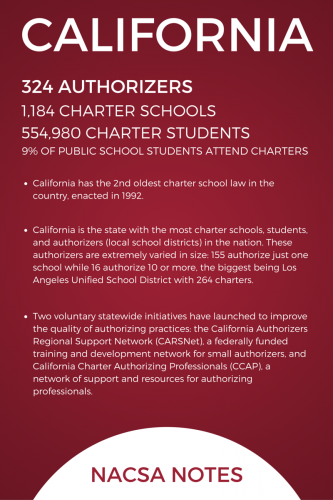

And so, you know, it was a chance to take on more—have a more manageable portfolio, but take a more active role in developing practice. That basically led me to work with our team at ACOE to write the grant that has now funded CARSNet, our statewide Charter Authorizers [Regional] Support Network.

NACSA: ‘The charter wars.’ Say more about that.

NACSA: ‘The charter wars.’ Say more about that.

Gail: Well, California’s a district authorizer state, primarily. Our statute is written [so] that approving a charter is the default position. So, a charter “shall be approved” unless there is evidence and specific factual findings on three specific criteria.

And districts are specifically not permitted to deny a charter based on financial impact on their own district, but it is a direct financial impact. So chartering has been contentious in California from the beginning. Partly that’s a union issue—most of our charters are not unionized. Partly it’s a financial issue.

The state went through some very tough times. Revenues declined or were deferred and every kid that walked out the door to a charter school was money out the door. Everybody who understands the economics of schools knows that you might lose one kid’s worth of revenue [but] you’re not saving one kid’s worth of costs. It’s just not a one-to-one correlation.

So, those ‘wars’ have been going on for years and continue.

NACSA: And that was part of what made it so tough to work those years within Oakland for you?

Gail: Well, yes, absolutely. Here’s a school district that has struggled for years, that had gone into state administration because they were running out of money. Bankrupt. Performance had been consistently poor. Large achievement gaps. Elected school board members [with political agendas]. And to approve a charter that would take kids away, to see charters performing well when the district schools might be stagnant—although, you know, Oakland has been really making a strong comeback—we didn’t have a board meeting with the charter item on the agenda [without] tons of people in the room and strong opposition being voiced to whatever it was. It didn’t really matter what side it was. It was always contentious.

Chocolate and Connection: Things That Sustain

NACSA: So how did you, as a human being—regardless of your role even professionally at that moment—how did you bolster yourself through those contentious meetings and keep going and wake up the next day and do the job?

Gail: How did I do that? Chocolate. A really wonderful husband. A belief that I was doing quality work.

NACSA: What did that quality work look like? How did you know it, recognize it, see it play out?

Gail: A couple different ways. I was fortunate to come into the office succeeding David Montes de Oca who had done a really great job in setting up the office, [and] had done some work with NACSA to set up protocols and procedures in the office. So, there was a foundation there. I felt that we had a consistent philosophy, consistent procedures, and we had data. We were working with the data on the schools.

We also had some validation from connecting with other authorizers. That was something I felt that I needed to do very early on because in the first six months, I felt pretty alone in the work. I had a small office and there were some great, dedicated people that we were working with; some of them are still there.

But [I] needed to hear from other people that they were feeling my pain. They were out there, and eventually we connected, and it was helpful to be able to pick up the phone and call somebody in L.A. and say, ‘Hey, guess what they just did?’ That was very helpful.

If you’ve done all that work and if you really know the school—whatever the decisions—or know the applicants, the proponents…I felt like most of the time [I] could walk into the board meeting with a conviction that what I was recommending was what was best for kids.