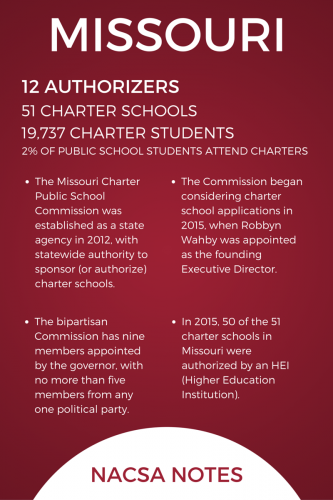

What follows are edited excerpts of our Story Suite conversation with Robbyn Wahby, founding Executive Director of the Missouri Charter Public School Commission. Robbyn also serves as a member of NACSA’s Board of Directors since 2015.

What follows are edited excerpts of our Story Suite conversation with Robbyn Wahby, founding Executive Director of the Missouri Charter Public School Commission. Robbyn also serves as a member of NACSA’s Board of Directors since 2015.

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Robbyn: I am a public school kid. [I] grew up in the city, in St. Louis. [I] went to the same high school my dad did. That, I think, is a very common conversation, particularly in Midwestern cities: you grow up, multiple generations [and] you live blocks away from where your parents grew up.

And yet, I didn’t have the same education that my father had. My father graduated from high school in 1944, left a few months after graduation, and went into the Second World War, like men did during that time. He had a stellar education. His 12 years of education (because there was no kindergarten at that time): [he had an] unbelievable vocabulary, [he] could do math in his head like you wouldn’t believe.

[He] came back from the war and didn’t go to college—didn’t take advantage of the GI bill—because no one he knew went to college. No one he grew up with, no one in his neighborhood, none of the guys that he was aboard ship with. It was different: you went to work and it was time to go to work. Years later, I talked to my dad about that, and he said that was his biggest regret in his life, that he didn’t go to college…

I graduated from high school in 1981, almost 40 years later. I went to 12 years of school, 13 with kindergarten. I went to [school] the same amount of time and you think about what happened between 1944 and 1981 and the fact that we were going to deliver the content and prepare someone in the same way, for two vastly different worlds! Then you speed up the pace of change today and my children are going to 12, 13 years of school: what’s happened between 1981 and 2015 in our world?

I got into the work of education because [it] didn’t make sense to me that I was not as prepared [as my dad]. I did not have the vocabulary. My dad drove a cab [for] 25 years, and what his knowledge [was]—what his skill set was—far outweighed what mine was as a college-educated person. How did we get to this? How are we not advancing? How is it not the reverse? How am I not leaving high school with more than my father would have left [with]?

I wanted to pursue that work. I worked in a lot of neighborhoods, did community development work, and saw that kids didn’t even get what I got—kids who were growing up in high-rise public housing, [in] immigrant families. So, I got into the work actually through community education.

What spoke to me mostly was that these were the public’s schools, not just public schools, and that communities had a right to determine what was going on in those buildings, based on their wants and needs. The one-size-fits-all didn’t work. It didn’t work for me; it certainly wasn’t going to work in the future, because the world is so different.

Doing School Reform Where the Children Are

Robbyn: I got into public education, [and] spent a decade working for our local district, working in community education. [I] saw so many difficult issues within the district: lack of quality teaching, lack of leadership in buildings, lack of empathy and understanding of the children, [and] the lack of access to services that would have made high-performing teachers really be able to deliver the promise for kids.

And an old thinking about what school looked like.

So I left working for the district and actually ran and became an elected school board member, because that was going to fix everything! And it did not. And so, I learned a lot about governance and what that meant for an urban district and the limitations of that. You think, working in a school: it’s the principal. Leading a school: it’s the administration. Oh, maybe it’s the governance. So in each place that you go, where do we make these corrections to this work?

I [kept] coming back to the public, [kept] coming back to the ownership of [the] community and to the directions of their schools, to the directions of whatever they need in their community.

I spent six years doing that work and actually [the] charter school law was passed during my time on the school board, as part of the desegregation settlement agreement in St. Louis and Kansas City.

I actually worked against the charter school legislation. Going outside the district was not going to help our district; [I thought] that we needed more public input inside, that we needed to break open the district, not replicate it on the outside.

What I saw for the vast number of [charter] schools, the first five, six years of the work, was a replication of the district. It wasn’t innovative—in my town, in my city. It was built by these rugged individualists who were going to try to do school differently and [they] really hired the same people and had the same sort of structures and systems. It just didn’t have all of the bureaucracy, but [it] really didn’t have any of the outcomes.

I joined the mayor’s office to work with him, believing that this connection between community and school was important. He did too, and he has been elected three more times since then, the longest serving mayor in the City of St. Louis. He has really made children and education front and center [in] his work.

I joined the mayor’s office to work with him, believing that this connection between community and school was important. He did too, and he has been elected three more times since then, the longest serving mayor in the City of St. Louis. He has really made children and education front and center [in] his work.

So, I joined him to work on education and convinced him that if we embraced the school district, if we would represent the public’s voice—the voice of the children—and work with this district to heal it, to help it advance, to break it open and provide a great place to work for the teachers who needed the things they needed—supplies and textbooks and leadership—could the families, then, choose to go to schools that were in their best interest, that met their family’s needs? We ran school board candidates and did that pathway to try to do that, and it wasn’t sustainable.

After all of that, I finally said, “Let’s take a look at this charter school work.”

NACSA: Robbyn, why wasn’t that way of making change happen within the district sustainable?

Robbyn: Well, systems over time—any institution over time—there is weight in time. You’ve been around a long time. You have those relationships. You have those systems in place, and even when they don’t work well—meaning having outcomes that we desire—they work well in might, entrenchment, and power. And when all of us have been through school that looks like that, it’s really hard to convince people that doing something completely different, outside of that system, would be better.

NACSA: So then, at that point, you started taking a look at the charter school option?

Robbyn: Yes: what else could we do? The mayor was pretty clear: we have to get good schools to kids. And I really took the approach of the entire system. You know the joke about why did Jesse James rob banks? Because that’s where the money was. Why do we do school reform with school districts? Because that’s where the children are.

We want to help the children. So we were forced to analyze that that didn’t work. We couldn’t sustain a big movement within an old district. You could not put [new] wine in old skins. Things that we’ve been told, right?

So the ‘what else [we] could do’ is [to] continue to go back to community. Go back to families living in neighborhoods: what do neighborhoods need? They need good schools. So, let’s try to do this a school at a time. But not in the way that we had traditionally seen that (adopt a school, replace the principal) and then, it’s still stuck in this big system.

Open For Business: Charters in St. Louis

Robbyn: We ‘Missourized’ the Indianapolis work [Robbyn credits Indy Mayor Peterson, and David Harris, then in the Indy Mayor’s Office, for their generous help and support] and then set a course of doing charter schools, with the exception of no authority: we had no authority to do any of this. So we just did it, which is great! There’s freedom in that, right? Who’s going to stop you, because [they] have no rules to stop you by.

So we simply used the [Indianapolis] application process, the vetting process. We, at the beginning, ran the prescription, whatever they were doing in Indianapolis, short of authorizing.

To compensate for that, the mayor got on the phone and called the local authorizers, which were universities, and said, ‘We’d like to get some great schools to St. Louis. We’re going to open up our doors. We’re putting that “Open For Business” sign out. If I put my name on it—if it’s good enough for me—if I believe this is a school that’s high quality and meets the demand of a neighborhood, would you be willing to consider authorizing it?’

And they said yes. That was really important.

A couple [additional] things were important. We also had Greg Richmond [NACSA President & CEO] come in. This is 2006, so things were happening with NACSA. Greg came through town and he met with us and with the mayor, and—I don’t know if he’ll remember this—but probably the most important statement about this work and our success came from this statement that Greg made. He said, “It’s not about competition with the school district. This is not ‘charters are good and district schools are not.’ This is about [that] we want quality public schools. Charters are a part of this conversation, and there’s deep work, important work, in this side of the equation that does not diminish all the other wonderful work and great things happening in the district.”

Removing the competition with district out of our vocabulary—our orientation—was incredibly helpful. It didn’t make it any easier, necessarily, to have these relationships with the district, but it was authentic for the mayor because he didn’t want that [competition], and we had just spent five years trying to make that school district better. We weren’t giving up on it. It just wasn’t its time yet, and other strategies were going to have to happen. But in the meantime, is there some way we can get good schools to kids? Yeah, let’s look at this. So Greg set that context of, ‘It’s always about quality, wherever kids can get it’ [which] really resonated with our mayor.

We also have a large private school and parochial school population, and we really didn’t want those families alienated from this conversation of quality either. It was their choice to send their children to a Catholic school or to an independent school. That’s fantastic. It should be quality as well. So that helped us set the stage for the work that we did in Missouri.